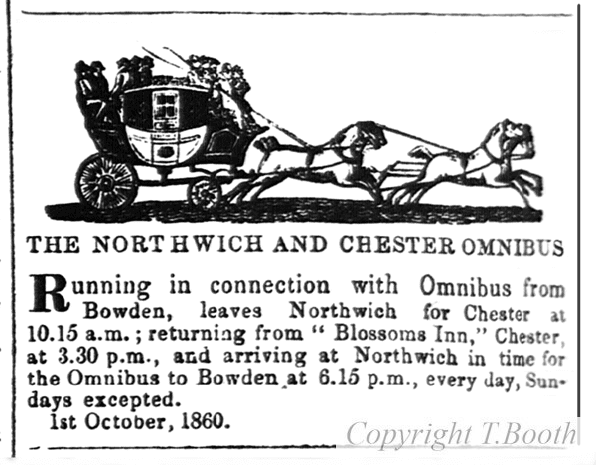

Before the coming of the railways stage coaches (often referred to as Mail Coaches), usually taking advantage of the much improved turnpike roads, criss crossed Britain in a bewildering number of routes connecting towns and cities. These coaches usually carried wealthy individuals, and more importantly the Kings mail, hence the armed guard that rode with the driver. Goods were moved by horse and cart, or pack horses between places not served by the canals. The rapid spread of the railways, providing safe comfortable travel for all classes of society, meant that, by the late 1850’s, the golden days of fast stage and mail coaches were well and truly over. Other coaches (commonly known as ‘Omnibuses’) did continue however into the early 1900’s. Whereas stage coaches had been the preserve of the ‘better off’, omnibus proprietors made a living providing transport for the lesser classes, filling in the transport gaps left by the railway companies. Before the construction of the Cheshire Midland, and later the West Cheshire Railways, an important stage coach stop on the Manchester – Chester road was at Hartford station (opened in 1837) where passengers and mails from Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, and London were transferred.

Advert in the Cheshire Observer, 29th of September 1860. It’s interesting to note that in this advert the omnibuses were running only as far as Bowden (Altrincham). The railway from Manchester to Altrincham, and Bowden, stations had opened in 1848. After that date it appears that passengers were obliged to change from coach to train, or vice versa, the coach service unable to compete with the fast and frequent rail link.

The proposals by the Cheshire Midland Railway in 1859 for a line from Altrincham, via Knutsford, to Northwich were generally welcomed, but objections were raised by some local retailers who suggested that some of their customers would travel out of the town for their shopping.

Local salt deposits, good frontage on the River Weaver Navigation, and the opening of the branch line to Winnington in 1870, made the site of Winnington hall and park an attractive proposition to the partnership of Brunner and Mond for the manufacture of Soda Ash. Huge volumes of coal and limestone would be needed and the railways could deliver these in bulk. Thanks to the railway, for better or for worse by 1873 the chemical industry in Northwich had begun.

Paying the price of salt. The railways had reduced the transport cost of coal, and thereby salt production and delivery, which helped push up demand from Britain’s booming industries. By 1878 the number of salt pans working in the Northwich district (Witton, Wincham and Marston) numbered 484 producing on average 587,000 tons of white salt per year and, by 1888 a total of 1.4 million tons were shipped by the 4 Cheshire salt towns of Middlewich, Northwich, Wheelock and Winsford annually. To evaporate this much salt required around 3/4 million tons of coal annually. The resulting pollution from burning so much coal (giving the town the nickname ‘The black country of Cheshire’) was compounded by the huge salt pans leaking brine on to the furnace fires beneath which, when burnt, produced hydrochloric acid. As a result, in 1884 the salt works came within the Alkali Act for reducing such pollution and were therefore subject to both inspection and prosecution. This did go some way to reducing both airborne pollution and brine losses from the pans.

In 1884 it was reported that out of 47 of the most important salt works in Cheshire, 44 were served by the Cheshire Lines Railway and by 1888 rock salt shipped from Northwich, by rail, amounted to 43,000 tons with another 94,000 tons shipped down the Weaver, the Winsford figures for river tonnages being double that of Northwich. It should be noted that the railway companies were under no obligation to provide special wagons for the transport of bulk salt. While the railways were successful in transporting both white and rock salt to domestic customers, it seems they were unable to compete with the River Weaver sending salt destined for export directly to Liverpool docks.

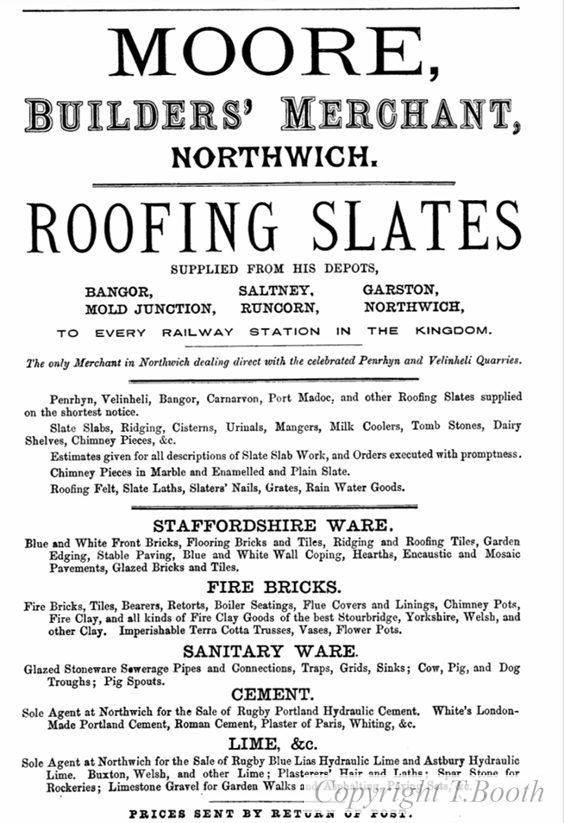

Moore’s builders’ merchant advert, 1874. Established in 1866, Moore’s builder’s merchant (in 1883 becoming Moore & Brock) was located in Sheath Street, with a frontage on the River Dane. In 1889 they moved to a site alongside the River Weaver at Barons Quay, and had their own private sidings connected to the branch line from Northwich station. Even by 1874 Moore’s had six depots, including two in North Wales, and according to their advert were able to send roofing slates (and presumably any other product) ‘TO EVERY RAILWAY STATION IN THE KINGDOM’. Cheshire Record Office.

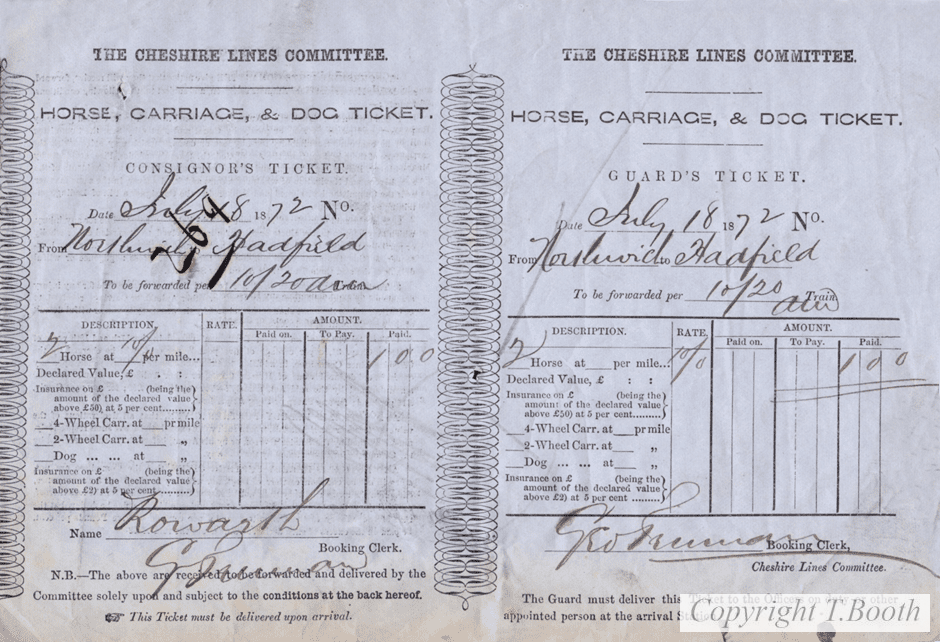

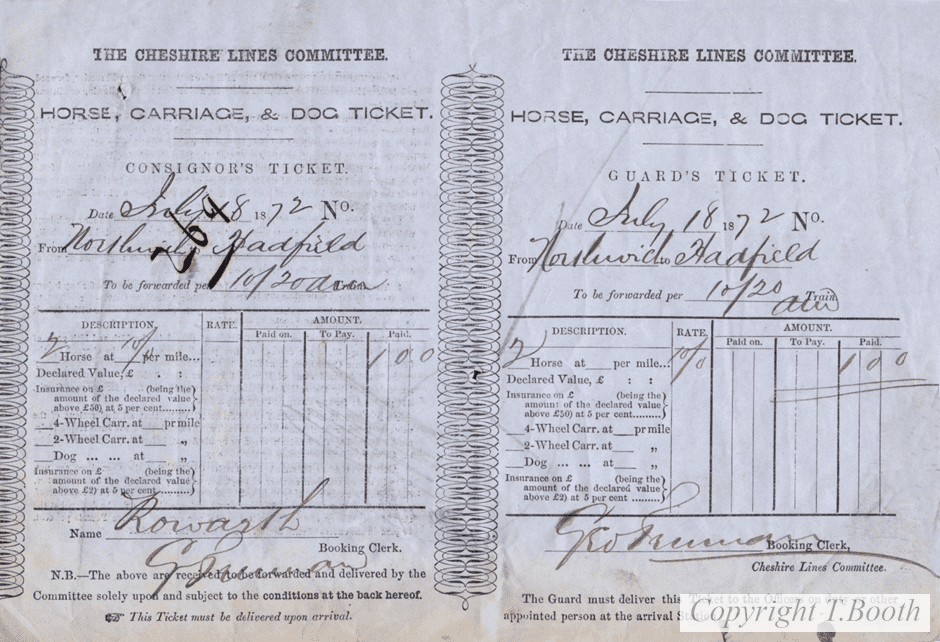

Cheshire Lines Northwich to Hadfield horse ticket, 18th of July 1872. The railway companies could not refuse any traffic that was offered to them. In this instance two horses have been sent from Northwich to Hadfield in Derbyshire. To cater for such traffic the railways had to build special vehicles. Here a CLC horse box would have to have been ordered by the station staff the previous day. This would have been brought to Northwich by regular goods train, but when loaded the horse box would be attached to a passenger train, and at some point on the journey attached to another passenger train to arrive at Hadfield the same day. Ten shillings (50p) per horse is something of a bargain today! T. Booth collection.

Cattle, sheep, pigs etc. were transported in cattle wagons attached to goods trains, but ‘prize bulls’ were moved in special ‘prize cattle’ vans. On arrival at the receiving station all livestock vehicles had to be cleaned and disinfected before being used again or returned. Goods yard staff and station porters had to be a ‘jack of all trades’ to cope with such traffic.

Before the coming of the railways the movement of livestock would have been undertaken by drovers, the animals being moved ‘on the hoof’, but taking livestock over such long distances would have been unthinkable.

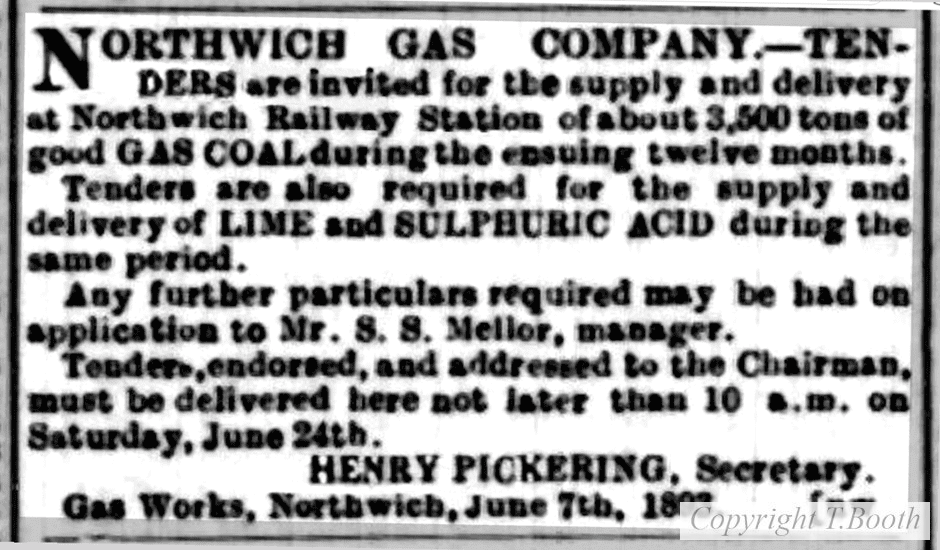

Northwich Gas Works public notice, Northwich Guardian, 17th of June 1893. Northwich gas works was established in 1834, with coal for their retorts probably arriving via the River Weaver and River Dane. The opening of the railway to Northwich in 1863 would have given the gas works, and several other industries in the town, access to a cheap, reliable, and plentiful supplies of coal from the Yorkshire and Lancashire coal fields. In c1905 the Northwich Gas Co. opened two sidings at the top of the old Leicester Street, situated near the end of the branch line from Northwich station to Barons Quay, in order to bring the rail borne coal nearer to their works. The coal was carted from there to the gas works in Timber Lane by Weedalls cartage contractors. Before the coming of the railway obtaining such huge volumes of coal for industrial and domestic use, many miles from the collieries, would have been virtually impossible. Northwich gas works closed on the 16th of May 1953.

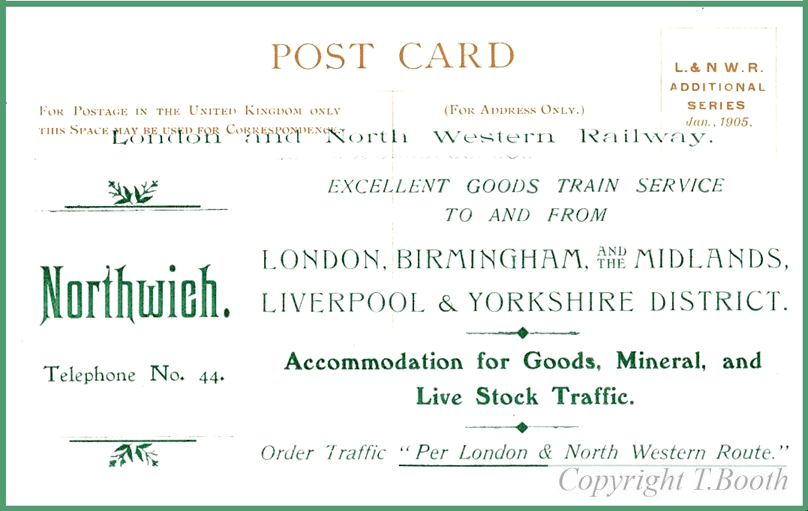

London & North Western Railway (LNWR) advertising post card, 1905. The LNWR branch line from Crewe via Sandbach to Northwich, and a connection near Greenbank to Liverpool and the north meant that despite Northwich station being owned and operated by the Cheshire Lines Railway, the LNWR appointed their own ‘goods agent’ (Thomas Worthington) at Northwich to deal with the considerable amount of traffic. T. Booth collection.

By the 1900’s nearly everyone’s lives were affected by the railways in one way or another in a way that these days it is difficult to comprehend. The railways had become ‘common carriers’, and as such could not refuse any traffic that was offered to them. At Northwich an endless flow of industrial and domestic traffic poured in and out of the station, goods yard, and marshalling yards. The Cheshire Lines employed four horses for van and lurry deliveries around Northwich, collecting and delivering to numerous shops and businesses, the railway stables being located on Manchester Road between where Tesco’s and McDonalds is now. In the goods yard, situated between the station and Manchester Road, livestock including cattle, horses, sheep, and pigs all had to be dealt with, along with domestic coal, hay, straw, sacks of grain, timber, barrels of oil and paraffin, iron and steel, machines, traction engines, boilers, and furniture vans. At the station itself, as well as passengers, they had to deal with luggage, newspapers, letters, parcels, milk, dogs, and racing pigeons to name just a few. The list it seems was endless.

Between the two World Wars the constant rise in the number of motor vehicles led to the serious loss of traffic from the railways. The Second World War did result in a huge increase in both passenger and freight traffic, but post war the pre-war decline continued at an even faster rate, eventually leading to branch line closures, closing of stations and goods yards, and the withdrawal of the facilities that the general public had depended on, and taken for granted not too many years before.